Proofs: Important information

Data for important traits like milk production, type, somatic cell score, fertility, calving ease and productive life are collected throughout the year on millions of dairy cows. However, analyzing this information is a big job, so scientists do it a couple times a year. Performance records are adjusted to age of cow and stage of lactation, and then each cow is compared with other cows that were in the same herd during the same time period. The result is a set of predicted transmitting abilities (PTA) for each animal – these are estimates of the genetic superiority (or inferiority) that a particular individual will pass to its offspring. Genetic information is produced for both sires and cows. But, since few farms have the luxury of using genetic indexes to select herd replacements from a large group of excess heifers, this article will focus on using genetic information for dairy sires.

Over 30 Traits to Consider

Each sire is evaluated for milk, fat, protein, fat percent, protein percent, productive life, somatic cell score, daughter pregnancy rate, estimated relative conception rate, service sire calving ease, daughter calving ease, service sire stillbirth rate, daughter stillbirth rate, final score, and 18 linear type traits. This means that you can get information for 32 traits on about 800 active A.I. bulls (roughly 600 Holstein) at any given time. Nobody has time to study all of this data, so what’s a sensible dairy producer to do?

A common, but incorrect, approach is to pick several traits and apply an independent culling level for each one. For example, you might decide that you’ll only use bulls that are at least +1,200 Milk, +0.05 Protein percent, +1.25 Udder Composite, and +1.00 Foot and Leg composite. This seems like a reasonable approach, but setting these levels is difficult, and the tendency for most people is to include too many traits. How could we leave out somatic cell score, fat percent, productive life or stature? As you keep adding traits, there will be fewer and fewer bulls that meet your criteria. And, more importantly, you’ll probably select a bunch of bulls that are mediocre for every trait. In other words, you’ll end up with a “jack of all trades” but a

master of none.

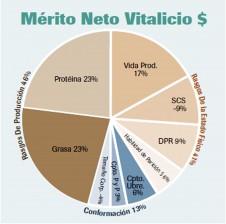

A better approach is to combine information from all of these traits into an economic index. Individual traits are weighted according to their economic importance, and genetic relationships between traits are taken into consideration. The primary index is Lifetime Net Merit (LNM)– this index measures the expected lifetime net profit of daughters of each dairy sire, relative to the breed average. Each of the breed associations produces an index of its own, but for the most part these are quite similar

to LNM, so I’ll limit my discussion to the three indexes provided by the USDA: LNM, Lifetime Cheese Merit (LCM) and Lifetime Fluid Merit (LFM).

For the vast majority of producers, LNM will be the index of choice. It considers production, health, fertility, calving ability, and functional type. The weights given to the production traits of milk, fat and protein are based on your bottom line – national average milk prices. About half the emphasis is on production (i.e., income), and the other half on functional traits (i.e., expenses). Note that somatic cell score gets a negative weight because we want a lower value for this trait. There is also a slight negative weight on body size – this reflects the differences in maintenance feed requirements for large versus small cows.

Two alternatives are offered for producers with unique milk payment situations. For farmers paid exclusively for components, with no premiums for milk volume, LCM would be an appropriate choice. It places more emphasis on protein yield, and excess milk volume is penalized. On the other hand, LFM may be a useful choice for farmers who are paid solely for milk volume. This index places much more emphasis on milk yield, and protein actually gets a weight of zero. In other words, if you don’t get paid for it, why produce it?

What about semen price? Obviously, this is a consideration, but cheap bulls are usually cheap for a good reason. In fact, if you have a good reproductive program, you will find the highest LNM bulls tend to be the best bargains. This will certainly be the case for virgin heifers because conception rates are quite high. You should always use your most expensive semen where it is most likely to result in a heifer calf; it will take twice as many units of semen to get a live calf from a high-producing mature cow than from a heifer. Lastly, remember there are a lot of good bulls available. Don’t rely on chasing the “hot” bull with limited semen availability.

What about reliability? Reliability measures the accuracy of the genetic information for a given sire and, hence, the variability in results that you should expect when using that bull in your herd. Bulls that have been progeny tested across many herds typically have reliability values of 80 percent or higher. Although bulls shouldn’t be selected or excluded based on reliability, it can be a guide as to how many units of semen should be purchased for a bull.